Sharing is caring!

By Maryam Henein, HoneyColony Original

Saturday morning cartoons with my sister and some Frosted Mini-Wheats with bananas on top. Hunting for milk-soaked Froot Loops in a big bowl of pink milk while staring at Toucan Sam’s pretty colors. Munching on Apple Jacks straight out of the (mini cereal) box. Ah those were the days.

These sugary bowls of “goodness” were a staple for me as a Coptic Egyptian girl in the late ’70s and ’80s. Later, in my teens, cereal gained admittance into my nocturnal life — Special K (because it was “healthier”) with girlfriends following a summer evening of clubbing, or a bowl of Quaker Oats during the nights leading up to my menstrual cycle.

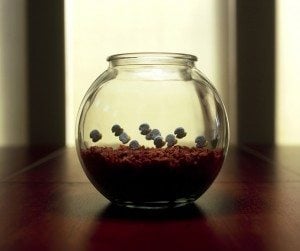

These memories were spurred by Cerealism, a photo series by 45-year-old photographer Ernie Button. His images — filled with nostalgia and innocence — transported m

e back to a time when Trix was for kids and ingredients and food intolerances didn’t matter. In Cerealism, the cereal becomes the character instead of those whacky mascots. Shredded wheat is transformed into rolling bales of hay against an arid terrain, and fish-shaped sugary puffs (from the limited edition of Finding Nemo cereal) become a part of an elegant deep-sea school. It’s cereal revisited on so many levels.

Today, cereal doesn’t bring out the tiger in me. A spoonful will make me sick — not only because it’s highly processed and highly sweetened, but because I’ve been a veteran member of the Gluten-Free Club for the past six years. For me, wheat and gluten are literally poisons. And I am not alone. According to Dr. Alessio Fasano, medical director for the Center for Celiac Research, approximately “18 million people (a.k.a. nearly everyone and his/her brother) have a newly discovered immune response called ‘gluten sensitivity.’”

So where did cereal get its humble beginnings, I now wondered? Ironically, a Dr. James Caleb Jackson invented the first breakfast cereal, “Granula,” in the late 1800s. His aim was to create foods that would help regulate the gastrointestinal system. Back then, diets were devoid of fiber, and our ancestors were gobbling a lot of meat for breakfast. Not surprisingly, Granula, which consisted of dense bran nuggets that required overnight soaking in order to choke down, wasn’t a hit.

Jackson worked at a sanatorium, a combination spa and hospital for the rich and famous where people learn(ed) to stay well. One of the sanatorium’s patrons was the American Christian pioneer Ellen G. White, who supposedly received a message from God insisting that human beings should reject meat. White went on to form the Seventh Day Adventist religion.

White never created her own breakfast cereal, but one of the members of her new church did: Dr. John H. Kellogg. Kellogg was a skilled surgeon and an advocate of abstinence who also worked at a sanatorium and, quite by accident, created the world-famous cornflakes. He and his brother left some cooked wheat sitting out too long and even though it had gone stale, they continued to process it by forcing it through rollers. They hoped for long sheets of dough, but to their surprise found flakes instead, which they toasted and served to their patients.

Beginning after World War II, big breakfast cereal companies such as Kellogg’s, Post, and General Mills started targeting children. The flour was refined to remove fiber, while sugar was added to tickle young taste buds. These new breakfast cereals began to look starkly different. For instance, Kellogg’s Sugar Smacks, created in 1953, contained 56 percent sugar by weight. A parade of cartoonish mascots also marched forth, such as the Rice Krispies elves, Tony the Tiger, and Trix the rabbit.

The rest is history — part of which Ernie Button captures evocatively in Cerealism. HoneyColony had the chance to speak with Button about his work, the food movement, politics, art, and culture in the context of an ever-changing cereal bowl.

HC: I read that you worked on this series on and off for more than a decade. What exactly sparked this idea, and how did you know the series was complete?

EB: Yes, I’ve worked on the series on and off for the past 10 years. When I wasn’t working on Cerealism, I explored other photographic subject matters. The inspiration for the Cerealism series started out mostly from an aesthetic perspective with a dash of nostalgia: On a trip to the grocery store, I noticed a change in the color and shapes of the newer cereals, as well as an increased emphasis on fun and excitement reflected in the packaging compared with some of the cereals I grew up with (like King Vitamin, a popular ’70s cereal).

New cereals are vivid and vibrant, with colors plucked directly from the rainbow. Cereals that I grew up with were all various shades of brown. The cereal aisle has evolved from mere nutrition with a splash of fun to food that is as entertaining as possible to eat.

As far as Cerealism being complete, yes, the bulk of the work is finished. However, if I find a new interesting cereal, I’ll most likely pick up a box and take a few photographs. Who knows where it will continue from there.

HC: I have such mixed feelings about cereal. It was a seemingly positive presence in my life that I associated with comfort, being cool, and feeling loved. Yet, today I can’t help but equate cereal with too much sugar, a bloated tummy, and our current agricultural landscape. What does cereal represent to you? And how has your perception of cereal changed throughout the years?

EB: My perception of cereal has also evolved. Cereal represents to me a carefree time where I didn’t have to think about a lot of things — including what I ate. The freedom and joy of being a kid! I don’t begrudge someone that still wants to eat cereal or can tolerate cereal better than my body can. Rather than being a staple of my diet, cereal is now more of an emotion or a feeling for me, as well as a form of creativity.

HC: On your website, you write that photography provides a forum for you “to communicate past and present, humor and concerns, observations and explorations.” You also mention that your “images often provide a voice to objects that are ignored and are frequently overlooked or taken for granted.” How does this apply to cereal?

EB: This line of thought can pertain to cereal in multiple ways: paying attention to the color or texture of the cereal, whether it’s more natural or artificial. How the shape of the cereal can reference things and objects outside of the cereal bowl. The subtle shift in the color of milk when the cereal is added. The wafting aroma cereal releases as the box or bag is opened. Subtle things that we can easily miss out on in the hustle and bustle of life.

HC: You hold an arts degree from Arizona State University. However, you are almost a completely self-taught photographer. How did you get into photography?

EB: I actually have a B.S. in economics and an M.S. in communication disorders. I’ve taken pictures and been interested in photography since my teenage years. But until my wife went to grad school to get her MFA in fine art painting, I really didn’t know that there was this whole world devoted to the making and creation as well as exhibition of art. The art world fascinated me and I wanted to be a part of it, even in a very small way. I took some classes at a local community college to give me a foundation in the basics of photography. After that, I was off and running.

HC: You are based in Phoenix and many of the pieces incorporate landscapes. Does cereal remind you of the Arizona terrain?

EB: Absolutely. I love the land and landscape photography. Arizona is a beautiful state in large part due to its diverse landscape, from the Grand Canyon to the Red Rocks of Sedona to the Sonoran Desert. Some of photography’s greats have spent time photographing Arizona, including Ansel Adams and Mark Klett. A magazine like Arizona Highways does an excellent job of introducing someone to this landscape.

Some of the cereal that is made up of mostly bran or fiber has the color and texture of the desert, so it’s an easy leap from there to a desert tableau. I used enlarged photographic prints of actual Arizona skies as backdrops to add that surreal quality that lends reality to the images.

HC: Is this the first time you’ve played with food?

EB: I’m currently working on a project titled Vanishing Spirits: The Dried Remains of Single-Malt Scotch. I got the idea while putting a used scotch glass into the dishwasher. I noted a film on the bottom of a glass, and when I inspected closer, I noted these fine, lacy lines. What I found through some experimentation is that these patterns and images are created with the small amount of single-malt scotch left in a glass after most of it has been consumed. The alcohol dries and leaves the sediment in various patterns. It’s a little like snowflakes — every time the scotch dries, the glass yields different patterns and results.

I’ve used colored lights to add life to the bottom of the glass, creating the illusion of landscape, terrestrial or extraterrestrial. Some images reference the celestial, something that the Hubble telescope may have taken or an image taken from space looking down on Earth. Circular images reference the round rim of a drinking glass and what the consumer might see if they were to look at the bottom of the glass after the scotch has dried. I titled each image with the specific scotch that created the rings and a three-digit number that has nothing to do with the age of the scotch but merely helps to differentiate between images.

HC: Are you interested in the food movement?

EB: I am, on a personal level. The more informed we are about what we eat, the better choices we’ll make about what we consume. I want to know as honestly and accurately what’s in the food that I purchase. One of the main lessons I learned as an undergrad studying economics is that a person’s dollar is essentially an economic “vote.”

We vote with money all the time: If you like the arts but don’t buy art from an artist, or don’t go to a local play or support the symphony, those things will eventually go away. They need your support, they need your economic vote. With regard to food, most of my economic vote goes to foods that are healthy and local and/or organic when possible (with the occasional purchase of cereal for creating art, of course).

HC: Is your art an expression of something bigger than yourself?

HC: Is your art an expression of something bigger than yourself?

EB: The goal of “Cerealism” is really about the enjoyment of cereal, a little bit of nostalgia, and the out-of-context use of cereal to create these alternate reality tableaux. My goal is not to demonize cereal or give anyone the impression that I am. I’m just having some serious fun with food. For me, as a middle-aged male, I recognize that I can’t eat an entire bowl of Cap’n Crunch with a good conscious anymore. But that’s not my intended take-away message from “Cerealism.” I can’t control what people take away from art in general or from my work. But my photography is, for me anyway, equal parts fun and thought-provoking.

I’ve been pleasantly surprised and honored that people like and respond positively to my images. The beauty of art is that we bring our own point of view to the work, regardless of the artist’s intentions. An image means different things to different people. I’ve had exhibitions where I am truly shocked at what people interpret the image to mean or even what they “see” in the image. Our interpretations are influenced by how we were raised, the type of day we had, our political views, whether we like or hate the color red.

HC: How many days does it take to create one of these? What took the most time?

EB: With some of the more complex images like the “Cheeramids,” it took about a week to build the base, glue the Cheerios, find the right backdrop, perfect the lighting. So that one and “French Toast and Crunch Canyon” probably took the most time to create and get right. Some of the more portrait-like images can be created in a day.

HC: Where do the fish come from?

EB: All the fish images have come from Finding Nemo cereal, including the clown fish, blue tang, and jellyfish. Some movies, mostly the big animated movie for the summer, have a special cereal to coincide with the marketing campaign for the movie. This past summer it was the Amazing Spider-Man cereal.

HC: With the “Bits of Magritte,” were you trying to spell in French? What is that, and what inspired it?

EB: “Bits of Magritte” is an ode to a painting by Rene Magritte, a Belgian surrealist painter. I had the good fortune of seeing a Magritte exhibition at the San Francisco MOMA. He has a famous painting of a pipe called “Ceci n’est pas une pipe,” meaning “this is not a pipe.” And so “Ceci n’est pas de la cereale” means “this is not cereal.” Yet it’s a photograph of cereal.

Photography works in the same way in that photographs are not “reality” — they’re constructions of how the photographer wants to present reality. There’s a photography exercise where you send 20 photographers to shoot the same location. You’ll get back 20 different takes or representations of that location because we all approach art with a slightly different perspective.

HC: Did you find common reactions depending on the city where you were exhibiting your work?

EB: I have a show coming up in Portland, Oregon, and I have shown my work in Portland before. The food movement is very strong there, and that city has a fantastic love of photography, and most people get the work, enjoy the work, see the quirkiness of the medium, and recognize that these cereals taken out of context can magnify something like the color or texture to the level of the unusual.

HC: This is sort of like an ode to cereal and American culture. Some shots get up close and personal. Would you agree?

EB: My own innate curiosity requires that close-up inspection, which influenced many of the final images. I suppose it could be viewed as a playful documentation of American culture through cereal. Cultures change and shift with the passing of time. What mattered to me as a child would probably not be of much interest to the children of today.

HC: Is there any particular food you’re really into right now?

EB: My wife makes a fantastic green smoothie.

HC: Are you working on anything else?

EB: As I mentioned earlier, I’m working on a few more images on the “Vanishing Spirits” project. I am hoping to be able to turn that into a book.

HC: To wrap up, just a couple more questions on cereal. Those manufacturers spend about $264 million a year marketing directly to children. And an average child is said to see about 600 TV commercials a year for cereal and 2 billion online banner ads promoting children’s cereals. Do you think this has gotten out of hand?

EB: I think it’s safe to say that a lot of things have gotten out of hand from an advertising and spending perspective.

HC: Back when I was young, I know my parents didn’t realize, for instance, that Honey Nut Cheerios contains a spoonful of sugar for every three spoonfuls of cereal! Do you think people’s perception of cereal is changing?

EB: Absolutely. And I think the manufacturers of cereal are hearing the message as well, because I have directly seen the cereal aisle change from when I first started this project. It’s shifted from “let’s have as much fun as possible” to a focus on increasing fiber and decreasing sugar. I’ll let the experts discuss and decide how successful they’ve been on that front.

- Tags: cereal, genetically modified, maryam henein, Quaker Oats, sugar, wheat